In the 19th century Bali comprised various kingdoms. During the colonial era the Dutch forcibly subjugated these different kingdoms, bringing the entire island under Dutch rule in 1908. In the wake of this painful conquest the Dutch deliberately set out to create the image of Bali as an idyllic, artistic paradise in order to gloss over the harsh and often bloody reality of its subjugation.

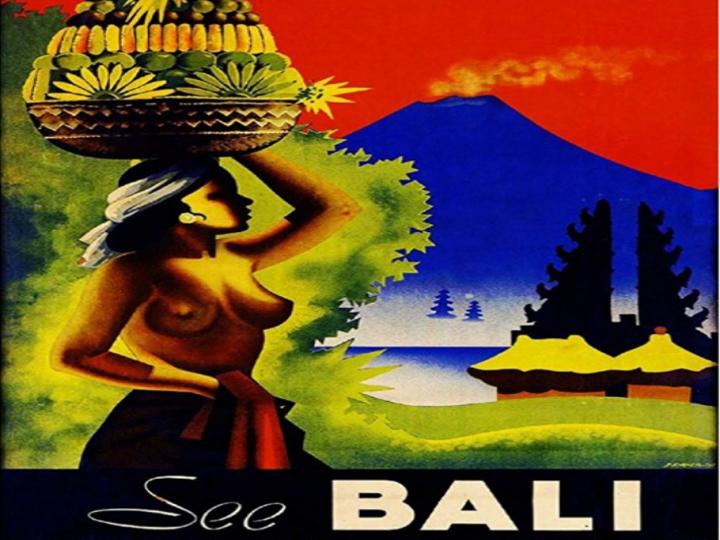

Art and photography, but also tourist advertising presented Bali as a paradise on earth, depicting scenes of peaceable village life and a thriving local culture. This propaganda was a key driver behind the rise of the tourist industry in the early 20th century.

Bali’s landscape and culture attracted not only tourists but also western artists. In Sanur, the German Neuhaus brothers made a living selling Balinese art to tourists. Other western artists, such as Walter Spies of Germany and the Dutchman Rudolf Bonnet, lived for a long time in Ubud during the 1920s. Together with local artists who had previously been court painters for Balinese rulers they created works intended primarily for the tourist market.